The books I’ll be releasing in 2025 both started life written in longhand on an iPad. In this post I want to talk a little about the processes I followed — different for each book — and how I’ve changed the way I write.

For now, the 2025 releases are called “the new book” and “the new new book”. The titles aren’t public yet.

To stay informed about those books, subscribe to the blog:

Earlier books

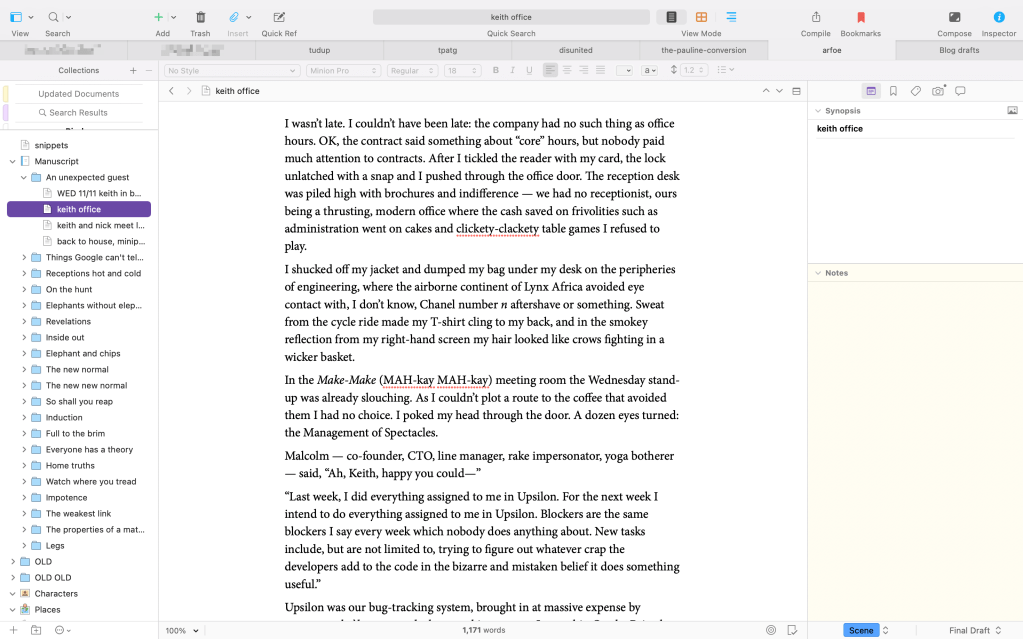

With my earlier books, I wrote the first draft in Scrivener — an app for writers available for Mac, iPad, and Windows. Each day I’d begin by rereading and revising what I’d written the previous day, and then I’d press on with new text.

Once the entire first draft was complete, I’d set it aside for a month or so to distance myself from the text, then read it and make notes (and no text changes). Then I’d use those notes to revise the manuscript in several complete passes.

When I thought a draft was “good enough” by some criteria, I’d send it to my trusted beta readers to gather feedback. Then I’d make further revisions until I was utterly lead-armed and fed up with the whole thing and forced myself to declare it Finished so I could hit Publish. (Finishing is the second-hardest thing about writing, after starting.)

The new new book

Confusingly, I wrote most of the new new book before I started writing the new book. I stopped because something was wrong with it and I wasn’t sure what, and I effectively abandoned it long before I started on the new book. But because I started the new new book first, I’ll deal with it first in this post.

The new new book started as unfocused noodling, using an Apple Pencil in the Goodnotes app on my iPad. I found this approach pretty liberating: as long as I had my iPad and my Apple Pencil, I could write. Train, coffee shop, bed, on holiday, wherever. I didn’t need to carry my laptop around with me. It’s ideal for noodling, but it turns out you can do more than noodle with it.

Goodnotes is aimed at students and similar who need to take notes, and has a handy tabbed interface that can represent lined notepaper. It can also convert handwriting to text, although it doesn’t do a good job with my scribbles. My plan was to tinker with ideas and characters and settings, and see if anything stuck. Paging through, I can see where the story started to emerge: I wrote “Feels like the start of the book” along the top of one page, in blue (and it still is, more or less).

At this stage I didn’t know any character names or locations. The main character was called XXX. There are other placeholder names, and insertions and crossings out. A classic first draft, as if on paper.

Without any word count mechanism, I could only estimate length. Over the course of several months I wrote almost the entire novel in Goodnotes in longhand, discovering plot and story as I went along, and thinking it was about half the length it was. And then I abandoned it. Well done, me.

When it came to revisiting the book last autumn, I started by rereading the first hundred virtual pages or so. That convinced me it was worth persevering with. Goodnotes, though, was not the place for revisions: I needed the text in Scrivener.

Ultimately I retyped the whole manuscript, as Goodnotes wasn’t good at reading my handwriting. And after those first hundred pages I was typing as I read — my first sight of those words in a couple of years. That was a surreal time. I’d forgotten much of what happened. I had no idea where the story would peter out. And this was, in effect, my first revision (I could de-clunk as I typed) as well as my first re-read. I had two years of detachment from the text, which brings a level of objectivity hard to replicate any other way.

When I finally reached the end of my handwriting — in the middle of a sentence, in the middle of a scene, apparently near the end of part 2 of the story — I could take a step back and decide what to do with it. Ultimately I mostly rewrote part 2 entirely within Scrivener, preserving and reshaping about half of what I’d originally written. (The original part 2 still exists, as a kind of branching of history I suppose.)

Some takeaways here:

- This book probably wouldn’t exist if I hadn’t handwritten it. It was written during downtime from the day job, when I was deliberately staying away from my laptop to avoid being drawn into work stuff.

- No live word count meant no targets to hit, no clear sense of progress, and also no pressure to finish.

- Retyping into Scrivener, though painful (literally), was the first revision — and it didn’t feel like one.

The new book

For the new book — started about a year after I abandoned the new new book — I wrote the first draft in a different app called Nebo, again on the iPad using an Apple Pencil. One of the writing modes within this app presents a lined surface that scrolls indefinitely (or at least until the app decides the file is too big). You scribble on the lines and the app attempts to recognise your handwriting — showing its (surprisingly accurate) interpretation above the current paragraph where you can correct it, often without changing any marks you made on the fake paper. You can copy what you’ve written as text to paste into another app. And it backs up what you write to the cloud (if you, cough, remember to turn it on).

You use pencil gestures to insert/remove line breaks and delete words, so you can edit existing text relatively easily. And there are the usual copy/paste options. Not exactly a word processor for your handwriting but pretty close.

It was good enough to let me revise what I’d written without the act feeling too much like a formal revision: it was more like scribbling in the margins of a draft. As with the earlier pre-iPad books, every day I’d revise the previous day’s writing — here by adding and deleting words. My brain called it writing and not revising, and so didn’t surface the ugh and here we go again feelings I sometimes get when I revise.

Also, revisions occurred organically and subtly when migrating the text from Nebo to Scrivener. When I finished handwriting a chapter, I’d go through its scenes in the app and check its interpretation of my scrawl was correct (subtle revision 1: changing things that felt wrong when I saw it again with a little freshness). And then I’d copy that text and paste it into Scrivener, and then take another pass through it (subtle revision 2: changing things that felt wrong when I saw it in a proper font, when the line breaks were different, and so on). And again these didn’t feel like they “used up” a couple of revisions: at this stage I didn’t feel as if I’d revised the text at all, even though I had.

With all chapters migrated, I went through a to-do list I’d already started writing, so I could fix the problems I’d spotted early — and this, finally, felt like my first full read-through.

Some takeaways:

- Good handwriting recognition changes the game: copy/paste from handwriting into Scrivener feels mildly miraculous.

- On the downside, Nebo’s recognition isn’t perfect and my ability to spot mistakes within Nebo isn’t perfect, meaning more typos in Scrivener

- I became reasonably accurate at estimating word counts (9 words/line multiplied by the number of complete lines) which gave me rough targets and progress: good psychological tools to help me keep going. I was averaging around 1500 words a day, for several weeks. Yes, my wrist ached.

- Subtle, hidden revisions reduce the feeling of drag, the slog, that sets in during the revision process — another psychological helper.

Summary

If I hadn’t handwritten these two books, they probably wouldn’t exist. That’s rather a mad thought.

The key question is: what will I do for the next book?

There’s a fair chance I’ll write longhand again in Nebo. The freedom to write anywhere at any time without the constraints of Scrivener is compelling. (Scrivener has an iPad app, but to use that I’d also want to get a separate keyboard so I could type properly, and at that point I essentially have a laptop again.)

Another advantage of Nebo: I can use its infinite canvas for diagrams and sketches, to scribble outlines or thoughts as needed.

I hope you enjoy these insights into my process: if so, please subscribe! I’m happy to answer any questions here, or on Bluesky or Threads – please get in touch.

Leave a comment